- No matter what the NGOs say, we need energy – cheap and effective energy.

- When energy prices go too high, inflation results.

- When inflation kicks in, consumer spending is lower.

I’ve got my java right next to me as I type this.

That’s my energy for right now.

My computer runs on electricity produced from coal, hydropower, or nuclear power.

Or natural gas.

Whenever I teach a class, I say, “Everything you are sitting on, wearing, or used for transportation to get here was either made with or runs on oil and natural gas.”

Too many people think energy magically sprouts from the ground and should be made cheaper.

They don’t understand the connection between our energy, production ability, and spending.

Today, with thanks again to Mark Rossano, the Sherlock of the Supply Chain, I will run through energy.

We’ll go from oil and gas through GDP to our spending.

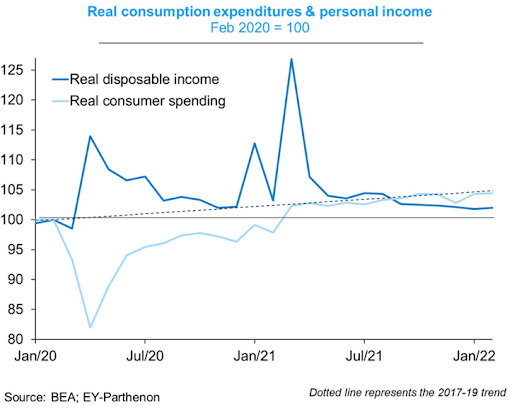

Every decision we make is based on how much disposable income we have. (That’s what’s left after taxes.)

But how much do our energy costs eat into that disposable income?

Let’s try to find out…

Energy: Oil and Gas

Energy is the cornerstone of the global supply chain.

Whether or not we admit it is a vastly different story.

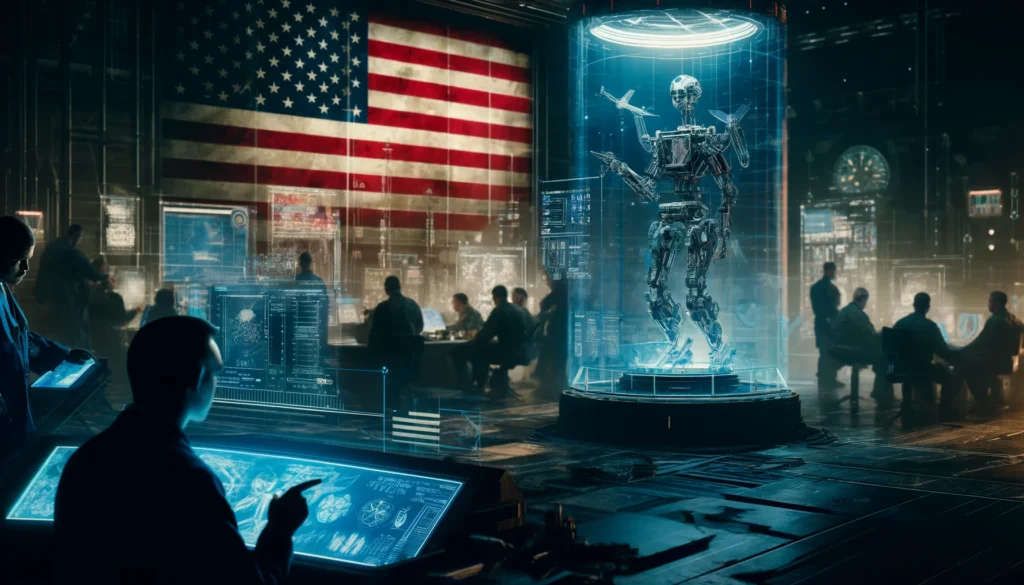

Natural gas prices have moved to a record during the “Shale Revolution,” just now taking out the 2007 highs.

Natural gas is a critical component of everything: electricity generation, heating homes, and powering facilities.

It’s also a key input to everything from petrochemical creation to refining and fertilizers.

Energy prices have risen across key variables driven by under-investment, political turmoil, and geopolitical shifts.

As supply remains constrained, we can only get a meaningful adjustment through demand reductions.

Another vital factor is diesel prices, which have been relentlessly rising.

Diesel prices have just hit a new record, driven by global shortfalls that are unlikely to fall back to normal in the near to intermediate term.

There is no quick solution to creating more diesel without a sharp drop in demand.

The last time we saw this kind of move was in 2008, and it only started to move lower after demand fell off a cliff.

Diesel prices hit every part of the supply chain, and given the current storage levels globally, we are in a tough spot to see this drop off without some extensive pain.

Diesel surcharges are now included in delivery breakdowns, and it has added more to the underlying cost of many items.

Typically, fuel and labor are straight pass-throughs to the end-user.

Diesel is more expensive than ever.

Diesel is more expensive than ever.

Diesel price this year (light blue) versus prior years’ performances Credit: Bloomberg

Got Crude?

When a refiner creates 1 barrel of diesel, it also creates about 2 barrels of gasoline, and it’s hard to adjust that ratio.

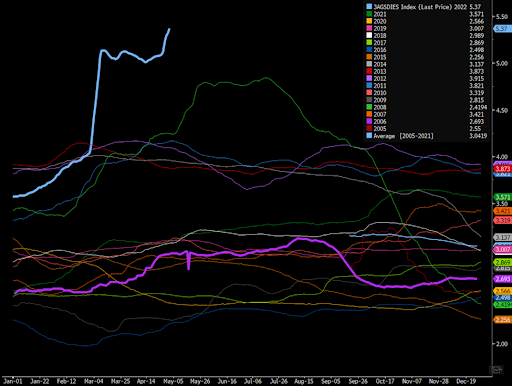

But a key issue is the type of crude available because there are a wide variety of crude grades.

Europe and the U.S. have stopped importing Iranian barrels and are shunning Urals (Russian crude), adding to the shortage of distillate.

I’ve mentioned before in the Rude this is one of the main reasons I oppose Russian sanctions. We simply need the Urals crude to make our fuel.

These barrels typically yield a higher distillate cut during the cracking process that creates different refined products like gasoline, diesel, kerosene, and propane.

The distillate is the liquid product condensed from a vapor during the distillation process.

The above is a helpful chart to see the different types of oils and where they sit on the sulfur and gravity axes.

Crude oil is typically measured by:

- sweet/sour (how much sulfur is in it)

- heavy vs. light (the API gravity or viscosity of it)

- TAN (acid)

Refiners will typically blend these different cargoes and adjust the cracker accordingly to run the varying qualities.

By removing Venezuela, Iran, and Russia from the mix, we are missing heavy barrels in the market.

This has driven up the price of replacement barrels.

So from the refiners’ perspective, they see all of their crucial input costs going up: natural gas, crude oil, and labor.

Refiners also have to deal with the storage of products, and gasoline/light distillate is a growing problem in Europe that is sitting on a seasonal record of the stuff.

In 2008, we had a surge in crude pricing mixed with peak demand that culminated in the Great Financial Crisis.

This time around, we have crude prices below 2008 peaks but many supply chain bottlenecks, including the Ukraine-Russian war.

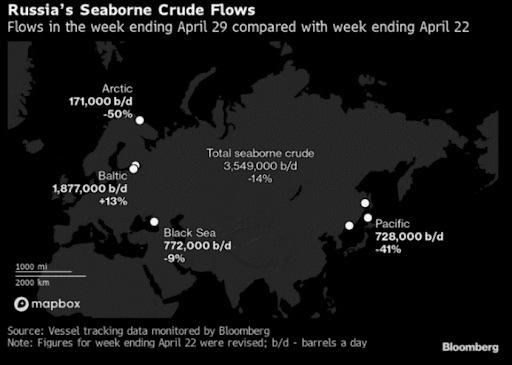

Russia is not only a prominent crude exporter but also exports a significant amount of diesel into the market.

Russia can’t risk shutting in facilities, so they will keep dumping into the market at any clearing price.

Differentials go as wide as $37 below Brent (UK) crude to keep things fluid.

A locked-down China has reduced its buying needs, leaving more Russian and West African crude in the markets.

But, Russian crude can’t flow into Europe and the U.S. because of sanctions (at least not at pre-Ukraine levels), while West Africa is reasonable but limited in the amount of diesel it produces.

In short, we still need Russian oil, no matter what the “English majors” running the West say.

Are Workers That Expensive?

Labor and fuel are typically a straight pass-through, only moving higher across the board.

As March-June typically sees a big hiring boost, we had employment costs move back to new highs.

Given the tightness in the labor market, companies are paying up to bring on new employees.

Inflation, but not as much Wage Inflation as you’d think

Consumer prices are already hitting John Q. Public hard.

Wages have failed to keep pace, which will keep the pressure on retail sales.

GDP, CPI, and Spending

The US consumer makes up 70.5% of GDP.

The G7 ex-US average consumer is 60% of GDP, which gives you an idea of how much the US consumer buys relative to his international cousins.

As the U.S. consumer goes, so does U.S. growth.

The slowdown is causing a big step up in inventories, resulting in a slowdown in new orders.

The consumer now faces a mountain of price increases, wages that have risen but not enough, and elevated inventories.

This is a recipe for “I’m going to skip the store this week” or “I’m not going to buy that (insert item) right now.”

The below chart shows the savings rate has taken a nosedive, while inflation rates push to a multi-decade record.

Credit: Bloomberg

The problem remains a fickle consumer, but the shifts are apparent: US consumers are still spending, but they’re doing so with more discretion.

Many people have already purchased items with government transfers, which is why a “fiscal” drag” is a real thing.

In the U.S., a typical American receives a check for $2,000 and will spend $5,000.

So not only were the needs met, plus those prices have gone up by over 30% with more pressure coming.

Spending on services should be a growth spot in Q2.

But as prices keep rising, we expect a significant drop off into the end of May/June.

And as interest rates rise, it will put more pressure on available credit as financial conditions only get tighter in the next few months.

The fiscal response (government) has already been tapped out.

With over 50% of our budget sourced from treasury bills, the cost of borrowing will rise.

Rising rates will also hit emerging markets even harder as global manufacturing output has already moved into contraction.

As global real wages continue to fall, so will economic growth.

Wrap Up

Energy is expensive, which leads to higher costs, which eats into disposable income, which eats into discretionary spending.

And since we’re not spending as much, manufacturing is down into contraction territory.

It seems like the natural result of unnaturally low interest rates, fatuous fiscal policy, and reckless monetary policy.

But hopefully, this gave you a roadmap from energy to end-user.

Until tomorrow.

All the best,

Freedom Financial News